Sinjar, Iraq – Under a gray winter sky in Sinjar, a long funeral procession winds its way to a holy Yazidi burial ground. Women ululate in grief, men carry coffins draped in white, and an entire community stands united in sorrow and resilience. In an emotional ceremony, the remains of an additional 32 Yazidi genocide victims – martyrs to their people – were finally handed back to their families for burial . Among them were 19 victims from the village of Kojo, a place now synonymous with Yazidi suffering, who were laid to rest at the mass grave of Kojo after taking them newly built genocide memorial monument . For the families, this day marks the end of a nearly decade-long wait to bury their loved ones on home soil. But it is also a stark reminder of the wounds that remain unhealed and the justice still beyond reach.

“For us, burying our fathers, mothers, brothers, and sisters is a relief and yet our pain only deepens”

says one Yazidi survivor at the ceremony.

“The genocide against Yazidis seems to have no end. We still don’t know when the other mass graves will be excavated so that we can find some closure” she lamented, tears in her eyes.

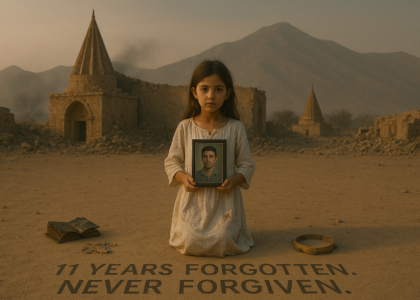

Her words capture the mix of anguish and resolve felt across the crowd. Nearly ten years after the Islamic State (ISIS) tried to annihilate the Yazidi community, families are finally reclaiming the remains of those who were murdered. But thousands of Yazidis are still missing, and the community’s long fight for recognition, accountability, and closure is far from over.

Survivor’s Pain and Resilience: Farida’s Story

Among the survivors of the Yazidi genocide is Farida Khalaf, who has become a voice for her people’s trauma and perseverance. In August 2014, Farida was an 19-year-old girl living in Kojo when ISIS militants stormed into her village. They came suddenly, heavily armed, we had no chance to escape, she recalls. The fighters separated families, ripping children from parents. Farida watched in horror as the militants rounded up the Yazidi men including her father and eldest brother and took them away. In the days that followed, ISIS would execute the men of Kojo in mass and enslave the women and girls . Farida herself was shoved onto a bus with dozens of other terrified young women, destined for the brutal slave markets of the ISIS caliphate.

“They removed our humanity piece by piece, until nothing was left but fear and despair” says Farida Khalaf, describing how ISIS treated its captives .

Farida endured unspeakable atrocities during her months in captivity; beatings, attempted rape, forced conversion, and the constant terror that she would be killed. Yet she never lost the will to survive. In a daring escape, Farida and a few other girls managed to slip away from their captors under cover of darkness. Today, Farida bears her scars with dignity and has become an outspoken advocate for Yazidi survivors. She has written a memoir of her ordeal and even addressed the United Nations to tell the world about the genocide that ISIS committed against her people. In one passionate plea before the UN Security Council, Farida urged world leaders to hold ISIS accountable for these abhorrent acts and to recognize the Yazidi genocide through concrete action. Though still only in her late twenties, Farida Khalaf’s voice carries the weight of an entire generation of Yazidis who refuse to be silenced by terror. Her testimony, and that of others like her, ensures that the suffering inflicted by ISIS is known and that the resilience of the Yazidi spirit shines through even the darkest story.

The Yazidi Genocide of August 2014

The tragedy that befell the Yazidis began in early August 2014, when the Islamic State launched a ruthless campaign to wipe out this ancient religious minority in northern Iraq. On August 3, 2014, ISIS fighters overran Sinjar district, home to one of the largest concentrations of Yazidis in the world. What followed was nothing less than a genocidal rampage. Approximately 400,000 Yazidis fled for their lives into the surrounding mountains or into Kurdistan, but tens of thousands were not so lucky . In a matter of days, an estimated 5,000 Yazidis were systematically massacred, and over 6,400 (mostly women and children) were abducted and enslaved by ISIS . The militants made no secret of their intent: they openly proclaimed that Yazidis, whose faith did not align with their ideology, should be exterminated or forced into slavery.

Entire villages were decimated. In village after village, ISIS separated men from women. Adult and teenage males-even boys as young as 12 were shot or beheaded if they refused to convert. Women and young children were dragged away to be sold in slave markets or given as spoils of war to ISIS fighters. One village, Kojo, witnessed particularly savage brutality and has become emblematic of the genocide. There, on August 15, 2014, ISIS rounded up all Yazidi males and executed them in groups, dumping their bodies in mass graves, while the women and children were taken captive to serve as slaves . By the time ISIS assault was over, the Yazidi heartland of Sinjar was virtually emptied of Yazidis. In addition to those killed or captured, the entire remaining population some tens of thousands of people spent days stranded on Mount Sinjar without food or water, desperate for rescue. Children and infants perished from dehydration on the mountain . It was a catastrophe that shook the world’s conscience.

This onslaught was later officially recognized as a genocide by the United Nations and many countries, given ISIS clear intent to destroy the Yazidi people . But for the survivors and the families of the victims, these events are not just recorded in reports, they are seared into memory. Nearly every Yazidi family was touched by the horror of August 2014, whether through the loss of a murdered relative or the unknown fate of an abducted loved one. A full decade later, thousands of Yazidi women and children who were enslaved by ISIS remain missing, their families still awaiting any word of them. The genocide is not history for the Yazidi community; it is a living reality that continues to unfold, shaping every funeral, every refugee camp, and every act of remembrance in Sinjar today.

Mass Graves and the Search for the Missing

In the years since ISIS defeat in Iraq, the evidence of their atrocities has been emerging from beneath Sinjar soil. The retreating terrorists left behind a landscape of mass graves shallow pits and ravines where they had cruelly disposed of Yazidi victims. Ninety-three mass grave sites connected to the Yazidi genocide have been documented so far across Sinjar . Each one holds the remains of fathers, mothers, sons, and daughters who vanished in 2014. Unearthing these sites and identifying the victims has become a sacred mission for the Yazidi community and the Iraqi authorities, supported by international partners.

The process is slow and agonizing. Of those 93 known mass graves, only 55 have been excavated to date . From these, roughly 750 sets of remains have been exhumed . Forensic teams carefully sift through dirt and bone fragments, often working by hand to preserve any personal items; a comb, a fragment of clothing, a simple pendant that might help identify the dead. Family members sometimes stand vigil during the exhumations, hoping to recognize a recovered item or simply to bear witness to the moment their loved ones are finally found. So far, 242 victims have been identified through DNA matching and other forensic methods, and returned to their families for proper burials . That leaves 508 exhumed Yazidi victims still unidentified, stored in Baghdad morgues awaiting names and relatives and hundreds more graves yet to be opened .

Every discovery carries a heavy weight of mixed emotions. There is grief, as families are confronted with the reality of a relative death, often years after clinging to hope that they might be found alive. Yet there is also a measure of solace: at least these families can finally hold funerals and lay their loved ones to rest according to Yazidi rites.

“We waited almost ten years to bring him home” said one father during the ceremony in Sinjar, referring to his eldest son whose bones were identified through DNA. “Now I know where he is. Now I can mourn him properly.”

For others, the wait goes on painfully. Many Yazidis still have no knowledge of the fate of their family members whether they lie in one of the unopened mass graves, or languish in captivity somewhere, or were killed and yet to be found. Each mass grave still hidden in the hills of Sinjar represents anguished families still searching for answers.

The work to excavate and identify the victims is ongoing, carried out by a coalition of dedicated teams. Iraqi Mass Graves Directorate and Medico-Legal Institute lead the forensic efforts, often operating in arduous conditions. They have been assisted by the United Nations Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes by Da’esh (UNITAD), which has provided expertise, technology, and manpower to ensure the excavations meet international standards . In March 2019, the first exhumations in Kojo were conducted with UNITAD support, in full view of the surviving Yazidi community, who gathered to observe and participate in the dignified recovery of their relatives . Similar efforts continued in October 2020 at other sites . This collaboration is not only about recovering remains; it is also about preserving evidence. Every bone and every bullet casing documented is a piece of the truth proof of the genocide that can be used in courts to bring ISIS perpetrators to justice.

Forensic investigators describe the Yazidi mass grave excavations as the most challenging of their careers, both technically and emotionally. Some gravesites are booby-trapped or in remote, rugged terrain; others contain commingled remains that are difficult to distinguish. DNA identification is painstaking and often delayed by limited laboratory capacity. Many Yazidi families were entirely wiped out, leaving no close relatives to give DNA samples for matching . And yet, despite these challenges, progress is being made inch by inch. Each time a skull or a bone is lifted gently from the ground, it is a moment of heartbreak but also a step toward honoring a promise: that the victims of this genocide will not be forgotten in anonymous pits, that they will be named and remembered. Each martyr remains represents a story of a life cut short and a family long quest for closure. The ongoing burials in Sinjar, like the one that reunited 32 victims with their families, are crucial acts of remembrance and resilience. They show that even in the face of unimaginable tragedy, the Yazidi community is determined to reclaim their dead and affirm that every single one of those lives mattered.

Recognition of Genocide and the Quest for Justice

As the Yazidis recover their loved ones and recount their stories, they are also striving to ensure that the world acknowledges the full enormity of what was done to them. The ISIS campaign in Sinjar was not a random tragedy; it was a deliberate genocide, and today there is a broad international consensus on this fact. A UN human rights investigation famously concluded that ISIS had the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, the Yazidi people, meeting the legal definition of genocide . In May 2021, UNITAD; the UN investigative team gathering evidence in Iraq, formally determined that the crimes against the Yazidis constitute genocide and crimes against humanity . Multiple countries have since come forward with official recognition. Germany’s Parliament passed a resolution in January 2023 declaring ISIS crimes against Yazidis a genocide, and the United Kingdom’s government followed suit in August 2023 on the nine-year anniversary of the attacks . Earlier, Belgium and the Netherlands had passed similar resolutions in 2021, and the European Parliament had recognized the Yazidi genocide as far back as 2016 . The United States also formally acknowledged the genocide: in 2016, the U.S. Secretary of State declared that ISIS was responsible for genocide against Yazidis (as well as other minority religions) . Since then, the U.S. Congress and governments of France, Canada, Australia, and others have all condemned ISIS actions as an act of genocide against the Yazidi people . This growing recognition by the international community matters. Each declaration not only honors the victims and survivors by affirming the truth of their experience, but also helps build pressure for justice and accountability.

Crucially, Iraq itself the country where the genocide took place has officially recognized the Yazidi genocide. In March 2021, the Iraqi Parliament enacted the Yazidi Survivors Law, which explicitly acknowledges that ISIS committed genocide against the Yazidis and other minorities . This landmark law goes beyond recognition: it provides for reparations and support to Yazidi survivors, including financial compensation, rehabilitation, and measures to rebuild the ruined communities. For Yazidis, this was a significant step by their own government towards validation of their suffering.

“At least they now call it genocide on paper, in our own country” one Yazidi activist said when the law passed. That means our people’s suffering is finally officially recognized after years of advocacy. The law, if fully implemented, will help widows, orphans, and survivors like Farida Khalaf to reclaim their lives with some government support, though many note that funding and enforcement of its provisions have lagged.

Recognition alone, however, is not enough. The Yazidi community rallying cry has been for justice; real justice; for the crimes committed against them. This means seeing the perpetrators held accountable in courts of law. It means the world not only naming the crime, but punishing the criminals. In this regard, progress has been painfully slow, but there have been some important steps. A handful of ISIS members have been prosecuted and convicted for their role in the Yazidi genocide. Notably, courts in Germany, operating under universal jurisdiction principles, have convicted several former ISIS militants for war crimes and genocide against Yazidis, including a case in which an ISIS fighter was found guilty of genocide for the death of a Yazidi child he enslaved . These landmark trials (the first of their kind in the world) set an example, but they involve only individual perpetrators. In Iraq, dozens of ISIS suspects have been tried and executed, but often under terrorism charges rather than specifically for genocide, and with little participation by Yazidi survivors. No international tribunal has been established for ISIS, and many Yazidi survivors feel a deep gap remains between the scale of the crimes and the global response.

Yazidi activists like Farida Khalaf and Nobel Peace Laureate Nadia Murad have been at the forefront of calling for a more robust justice process. Farida, in her address to the UN Security Council, earnestly appealed for the creation of a special international court or mechanism to prosecute ISIS abhorrent acts and genocide . She reminded world leaders that over 2,700 Yazidis are still missing, women and children who were kidnapped in 2014 and have not been found and urged that finding them must be a priority . Farida also implored the Council and Iraqi allies to help rebuild Sinjar, noting that an entire community remains displaced and in ruins . Justice, Yazidi advocates say, has many facets. It is criminal accountability, but it is also rebuilding homes, providing therapy for trauma, and giving Yazidi children a chance at a future. It means ensuring that the genocide is taught in history books so it cannot be repeated. And it requires the international community to stand in solidarity with the Yazidis for the long haul not just in words, but in actions and resources.

Never Forget: A Call to the World

As the sun sets over Sinjar on the day of the funerals, the freshly covered graves are adorned with candles and framed photographs of those who finally found a resting place. Each grave is not just a site of grief; it is a symbol of resilience and a call to action. Every one of these martyrs was an individual with dreams, laughter, and love their lives mattered, and their deaths demand justice. The Yazidi community has a saying: To forget the martyrs would be to kill them a second time.†They are determined that the world must not forget. The genocide against the Yazidis is one of the darkest chapters of the 21st century, and its aftermath is still unfolding today. If the world turns away now, these wounds will never truly heal.

For the international community, never forget must be more than an empty slogan. It must mean support for those still suffering and concrete efforts to prevent such atrocities in the future. About 2,700 Yazidis remain missing to this day many of them young women and children whose abduction has never been accounted for . Finding them or learning their fate is a humanitarian imperative. Thousands of Yazidis are still living in displacement camps, unable to return home. Rebuilding Sinjar, which was reduced to rubble and remains insecure, is essential to restoring this community dignity and way of life . Countries that have pledged support must follow through with funding to construct houses, schools, and hospitals, and to restore the economy of this once-vibrant region. Psychological support programs are desperately needed for survivors (especially for women who escaped ISIS captivity and children who spent formative years under terror). The Yazidi Survivors Law is a start, but it needs robust implementation and international backing to truly make a difference in survivors lives.

Above all, accountability must be pursued relentlessly. The horror that unfolded on Sinjar mountaintops and plains should serve as a warning to the world. The perpetrators of genocide no matter how long it takes must know that justice will catch up to them. Whether through Iraqi courts, international tribunals, or national prosecutions in countries where ISIS members are found, every effort should be made to investigate and prosecute those who orchestrated the murder, rape, and enslavement of the Yazidis. This is not only to punish the guilty, but to honor the memory of the victims. Every verdict that acknowledges a Yazidi suffering is, in its own way, a form of validation and solace for the survivors. It tells them: the world believes you, and what happened to you was an unforgivable crime.

The handover of 32 Yazidi martyrs remains to their families in Sinjar is a milestone born of both tragedy and hope. It took years of advocacy, forensic work, and global pressure to arrive at this day. As the coffins were lowered into the ground amid prayers and tears, the Yazidi community demonstrated that they are down but not defeated. Their spirit endures in the face of what can only be described as evil. Now it falls to all of us international organizations, governments, and ordinary people of conscience to stand with them. We must ensure that the Yazidi genocide is remembered not just as a dark moment in history, but as a turning point that galvanized the world to protect vulnerable communities and to hold perpetrators of genocide to account. The story of the Yazidis is one of unimaginable pain, but also of survival and courage. In honoring their martyrs, in listening to survivors like Farida Khalaf, and in demanding justice, we affirm a simple truth: even in the aftermath of genocide, human dignity and hope can prevail.

Never forget. The world owes this to the Yazidis and to all victims of genocide, present and future. Each time a victim remains are returned and a Yazidi mother or father can finally whisper a last goodbye, we are reminded of why this fight for justice matters. It matters for one community in northern Iraq that has suffered beyond belief. And it matters for humanity as a whole, as we strive to ensure that the promise of never again is kept. The Yazidi genocide must never be forgotten and the pursuit of justice must continue until the last mass grave is excavated, the last survivor’s voice is heard, and the last perpetrator is held to account.